A Central Indiana Farmer’s Thoughts on the Farm Bill: Why It Matters to Me and Why It Should Matter to You.

The U.S. Farm Bill is an extremely complicated and huge piece of legislature. The reason it’s so huge is its authors must (as best they can) apply a nation-wide policy to a local area and its specific crops. Even though the Farm Bill has been around since the Great Depression, it gets an update every 3 to 5 years. 2014 was a year for an update, and even in 2015, the fields are still buzzing with talk about all things “Farm Bill”.

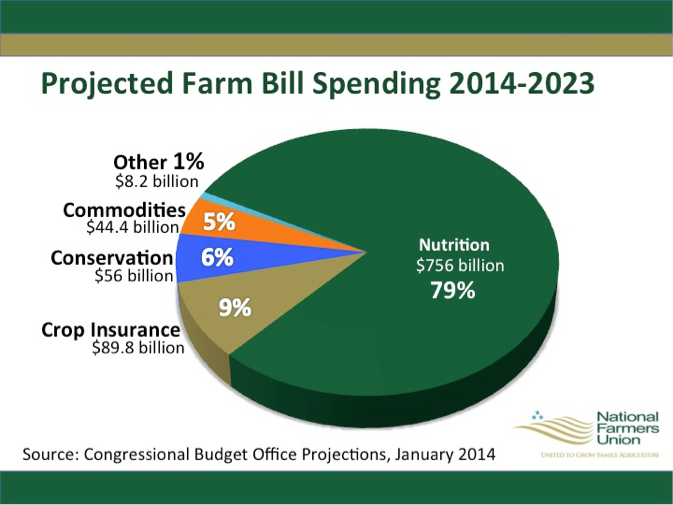

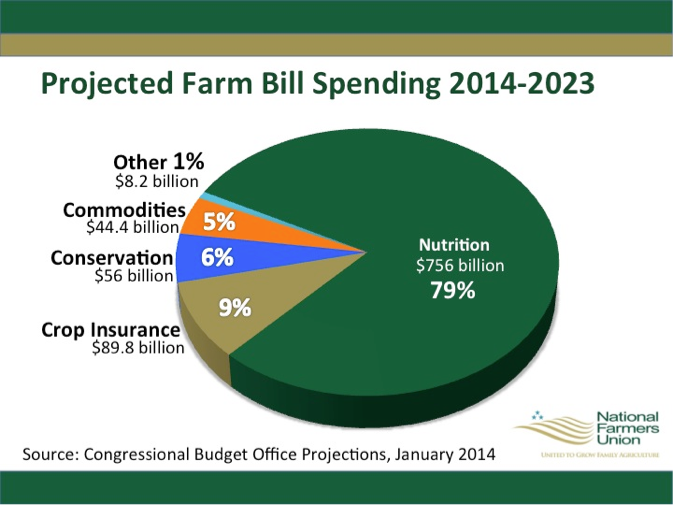

What the general public may not realize is that the Farm Bill is very poorly named. About 80% of the funding of the “farm” bill goes to nutrition programs such as Food Stamps (SNAP) and school lunch programs. Only about 9% (89.8 Billion) of the over $950 Billion is actually earmarked for Farmer Crop Insurance (which is what most people think of it as).

And as a result of this and just being a conservative Central Indiana corn and soybean farmer, I really struggle to support it, and feel I have a good reason for this. But I also realize that we have created quite a monster over the years and as a result, there is going to be no perfect answer.

NOTE: Here at Lamb Farms, we are trying to decide what our participation level will be in the newest version of the Farm Bill. The purpose of this post is to share our thoughts and concerns regarding our participation in the Farm Bill and by sharing, hope we can help others work through issues too.

Overview of the Farm Bill

The reason our nation started a Farm Bill is a sound one.

But like so many other government initiatives, it has morphed into things that weren’t part of the original intent. I have been an Indiana farmer over the past twenty-five years. I have a pretty good idea how the farm bill works here in our state, but my view is limited to that perspective. I can’t speak for all the farmers across our country that the farm bill serves.

But one thing you can’t argue about: The good, bad and ugly of it all boils down to these three words:

Protection vs. Entitlement

The argument for the Farm Bill is:

- It works to provide a safe reliable food supply

- It protects agricultural areas from major economic disaster, not just for the farmer, but because large areas of our country depend on agriculture for economic survival.

- It’s a place for sharing the cost of conservation practices that benefit our country as a whole.

I can’t begin to try to explain how the farm bill works as a whole, but the crop insurance portion, in plain english, can be thought of as a safety net. It tries to play the role of safety net to peanut farmers, cotton farmers, corn farmers, soybean farmers and every other kind of farmer in every corner of the country with varying weather patterns and market infrastructures.

I see all of this.

The argument against the Farm Bill is:

- This “government program”, as we farmers call it, has become an entitlement program for many farmers. Across the U.S. Farmers feel entitled to something because we produce food. Of course it didn’t start out this way, but over time we tend to forget how we got to where we are.

So How Did We Get Here?

Entitlement has come from a series of steps over time. Here’s a breakdown of some of those steps that have led to where we are today.d

1983: PIK Year

I remember 1983 was known as the Payment-in-kind or “PIK” year. That year, farmers had the option of setting aside certain portions of their cropland to grassland and not raising a harvestable crop on it.

It was an effort to control supply and therefore maintain crop prices. The government basically paid the farmer a set amount of money per acre to not farm a portion of his land.

This kind of program lasted for several years and eventually failed because farmers got really good at knowing where the least productive “wet hole” was on each farm and did not farm that part (but still got paid for it).

The reality was that the supply didn’t drop much and all the taxpayers made up the market to the farmer.

1990: Market Approach

The 1990 Farm Bill started to move the program to a more “market oriented” approach.

This was due in part to the fact that we needed to be able to have free trade with our neighboring countries. The U.S. government could not control the supply of one particular crop in order to regulate the price of that crop, especially as it dealt with other countries.

As a result of this, since the 1990’s, farmers became accustomed to what is called “direct payments” based on the yield and crop history of a certain farm.

As farmers, we would sign up our farms and the government would send us a check – it usually came to around $20 to $30 per acre. There was a payment limit as each entity could only get $40,000 in direct payments.

When this provision first came in, many family operations like ours simply divided up their farms into individual names and got around the payment limitation by having multiple entities.

I am somewhat sorry to say that our farm did this for a few years.

Looking back at that time, I would say we did that because we were just following what we were led to believe was just the “way it is done.”

There never seemed to be much question about whether something was right or not.

1990’s – Early 2000’s: FRUSTRATION

Over the next few years, the frustrations mounted as we learned of new things that we needed to do in order to keep our “entities” legal for the program. As we adapted more and more of our bookkeeping to reflect the individual entities, we had to work much harder to do a good job of evaluating our operation as a whole.

Before long, it started to make us really uncomfortable. The chance of being audited seemed fairly remote, but our ability to do everything absolutely right on paper seemed to be increasingly more difficult.

It just started to feel wrong.

We quit the extra entities and for many years now, we have only operated as Lamb Farms Inc. This leaves a lot of money on the table each year, but it is what it is. We are one family farm.

2005: Management = Control

During the past decade, we have started utilizing Federal Crop Insurance. This works just like any other insurance except for one thing:

- The risk of a crop failure across a large area is big enough that no crop insurance company could afford to underwrite it. If they could, no farmer could afford to pay the premium.

That is why about half of the premium for our crop insurance is paid by the government. We pay somewhere between $30 and $70 per acre for crop insurance.

If we have a failure, we’re covered. No need for government “disaster payments.”

If we don’t buy the insurance… tough.

I like this.

The government helps put us in a position to make a management decision that limits our risk, but we are still in control.

2014: The Good, The Bad & The Ugly Continues

Fast forwarding to 2013, as the battle started to brew over the 2014 Farm Bill, there were several things that we wanted to see. At the top – eliminate direct payments and separate the true “farm” bill from the “nutrition” bill.

Here’s what we actually got:

The Good in the 2014 Farm Bill – It Eliminates Direct Payments

One thing that everyone wanted to see was the elimination of direct payments.

It is just tough to justify a payment that really doesn’t correlate to any farming condition we are facing. I have hated it for years.

This was a payment that had been around long enough that it was just part of the budget for crop plans. In the end, the payments ended up in the pockets of the landowners…maybe the landowner was the farmer, but more likely the landowner rented the farm out.

Either way, if the payment went away, the budgets would just need to be adjusted over some time and the margins should not be affected. Politically, the payments were a no-brainer to eliminate. Farmers have had some of the best financial years in history and it doesn’t look good giving millions to them for no obvious reason.

I was very glad when they finally announced that direct payments were going to be eliminated.

The disappointing part was that like most government programs, the government really didn’t want to give up the money. And therein lies a problem that can make a good thing “not so good” (Refer to “ugly” section below).

The Bad – “Farm” Bill and “Nutrition” Bill Remain Tied

Another thing we wanted to see happen in this version of the farm bill would be to separate the true “farm” bill from the “nutrition” portion of the bill. I would love it if each portion of the bill had to stand for itself.

The farm lobby wants to keep it together, because they are afraid of losing the urban vote for the parts of the farm bill that are good.

The “welfare” lobby wants to keep it together because passing a “farm bill” sounds a lot better than passing a welfare bill. You rarely hear news about welfare funding because it is buried in something called a Farm Bill.

I was proud of our Indiana Representative Marlin Stutzman who tried separating the two. Unfortunately, both sides of the lobby are afraid to do that. The 2014 Farm Bill keeps the two tied together. I think it’s a shame when bills can’t stand on their own.

The Ugly – New Programs, More Work

The government saved 5 billion dollars on direct payments but decided they didn’t want to give it back to the taxpayer.

The government had been hearing from farmers that we liked the insurance. We like making a management decision to pay into a system that gives us a real safety net.

So, they decided if we like that program, they’ll just add the direct payment money like an insurance program. I don’t like that idea anyway, but if they are going to do it they should at least just add the money to the insurance program that is in place.

Instead, they created a brand new program that is like it’s own insurance program. Actually, they created three new programs that we get to choose from. For a Central Indiana corn and soybean farmer, it appears that only one of them will make sense.

Now we get to update our base acres for all of our farms. Then we get to look up our yield history on each of our farms for the five years of 2008 to 2012. In our case, it’s a little tougher since we raise popcorn, seed corn, and waxy corn instead of commercial corn.

Since our specialty crops don’t yield as well as commercial corn, our yield history is lower to begin with. So if you try to produce something extra by raising a specialty crop, you actually get penalized when it comes to qualifying for a government program.

There have been countless hours of training and program development put in by the Farm Service Agency staff across the country. I will spend hours getting our farms signed up, along with thousands of other farmers.

So why does it upset me so much to have to work for something that is supposed to be good for us?

Because we don’t need it.

I know that there is a great deal of uncertainty in the coming years with commodity prices as low as they are. And I understand that times can get tougher.

But we have had such good years in the last four years, even while we were still receiving direct payments. 2012 was a significant drought year, but because of crop insurance, we still had a very profitable year.

My Dad has always said it is more important to manage well in the good years than it is in the tough years. Farmers don’t have an excuse to not be ready to buckle down for an occasional “lean” year or two.

The other thing that bothers me is just philosophical.

When we go to a meeting of farmers or our Farm Bureau, we never seem to look at the big picture. As farmers, we are trained to always ask for more. When we are presented with a government program, we just attack it like any other business decision:

- Which hybrid should we choose?

- How much should we pay for cash rent?

- How can I get the most return from the government?

If we are good managers, we just take advantage of everything we can.

I hate to say it, but the word entitlement seems to fit the attitude of most involved in agriculture.

So, with all that said, what does it mean to us?

I don’t intend to make this more than it is or to be over-dramatic. I pray we all just really strive to be farmers with character and integrity. And with that, here are questions I have for my fellow farmers:

- If we don’t agree with taking money from our neighbors for something we don’t need, should we do it?

- Where does the line form between good business decisions and an entitlement mentality?

- If the agriculture community gives in to the temptation of taking unnecessary government handouts, have we lost the backbone of any possible conservative attitude still in this country?

Thomas Jefferson was opposed to slavery, yet he owned slaves until he died. It is one thing to say we oppose the philosophy of the Farm Bill, but another to reject the benefits it offers.

I believe the big picture of using unnecessary government payments will hurt agriculture in the long run. My Dad always says that in order to really make money, you either have to add value to something or take risk or both.

Risk management should be an important part of our farm management efforts, but that should be done as much as possible in the private sector.

The more the government tries to eliminate risk, the more we move toward a socialist mentality.

- We all become equal.

- Mediocrity is the goal.

- There is no motivation for anything else.

Parting Thoughts

With all that said, the reality is we may or may not sign up all or part of our farms.

The operator of a farm in 2014 is the responsible party to sign that particular farm up for the government program. We will not make the decision to decline the payment on a rented farm without discussing the impact with the landowner.

We realize the decision we make will be in place for the next four years, so the crystal ball gets a little foggy when looking out that far.

My head tells me to be wise.

If we have four years of really tough economic times, we may really appreciate the Farm Bill. Also, if we don’t take the money, the government sure isn’t going to save it… I’m pretty sure we would spend it more wisely.

My heart tells me to suck it up and go it alone.

If we don’t sign up, it won’t save us anything but time. Yet it might have some pretty big opportunity cost. I like the independence.

The reality is that there is not a good reason to pass it up – except for peace of mind. And each of us must determine our own value to that.

I know where I stand. How about you?